Misconceptions around China’s Real Estate Industry Woes

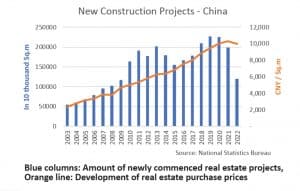

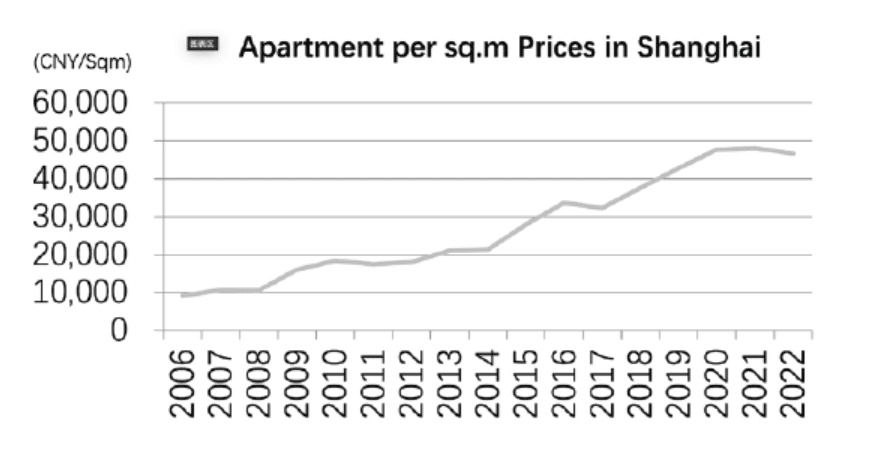

With the quasi-bankruptcy of Evergrande and other Chinese real estate developers and a significant drop in apartment prices for the first time in about twenty years, it’s not surprising that talk about the bursting of a China real estate bubble and market crash is once again making the rounds. China bears have been predicting just such an economic catastrophe for well over a decade: are we finally seeing it happen?

The developer bankruptcies have been triggered by China implementing its so-called ‘three red lines’ policies last year, which put real estate developers in a very difficult spot by drastically raising their equity requirements while at the same time cutting access to external funding. This made it difficult for them to launch new projects, and forced some to halt work on ongoing projects. Many home buyers who invested in these unfinished properties have discontinued their monthly payments until construction work resumes.

Banks who lent money to the failing developers — sometimes enormous amounts, and often without performing solid due diligence — are also among the policy’s casualties. The risk exposure to banks is especially serious in regions where demand for apartments is far less than it is in China’s wealthy east-coast cities.

Yet while developers, banks, homeowners and other affected entities are suffering financial losses and other forms of hardship, it appears that the government is by and large achieving just what it set out to do: Reigning in real estate developers while at the same time avoiding a sharp increase in home prices due to the subsequent slowdown in new supply that would inevitably follow.

Beijing’s goal in cooling down the industry is to ultimately reduce upward pressure on home prices, and redirect some of the disproportionate amount of investment going into real estate towards other industries and so create a more balanced economy, among other reasons.

The developer bankruptcies, liquidity problems at banks and other adverse situations that have arisen may be seen as a kind of collateral damage of the ‘three red lines’, which can be seen as a calculated shift from a free-market approach to a more regulated and planned approach towards governing the real estate sector. The government has already acted to mitigate some of this collateral damage by establishing a ‘rescue’ fund to ensure completion of residential projects that developers have halted.

It is very unlikely that the central government wants or would allow its construction and real estate industry — which contributes about 28% to the Chinese GDP — to suddenly collapse. If in the future construction and real estate contribute only 15-25% to the GDP, then that is in line with expectations for a country that nowadays is a far more developed economy than twenty years ago.

Should the problems turnout to be worse than anticipated then the government can at any point in time loosen its restrictions. For example, it could lower its equity requirements for developers, which were originally at about 10% and are currently at 50%, to somewhere around, say 25%.

Similarly, banks can again begin to provide loans – so long as they perform due diligence – to real estate developers that meet the government’s new requirements, and in the end the market may end up a more stable and healthy one.

In terms of stability of China’s residential real estate market, it’s worth noting that about two decades ago, it took 50 years in rental income to pay for an apartment in a city like Shanghai; in other words, rental returns stood at only about 2%. In a city like Frankfurt, it took around only 20 years of rental income to pay for an apartment, indicating a return of about 5%. Nowadays that gap has narrowed: it takes about 30 years in a city like Frankfurt and about 38 years in a city like Shanghai. With these multiples of 30 vs. 38 in mind, the market actually appears to be healthier today than some years ago.